Woodstock ’69 Crowd Was Moments From ‘Mass Electrocution’

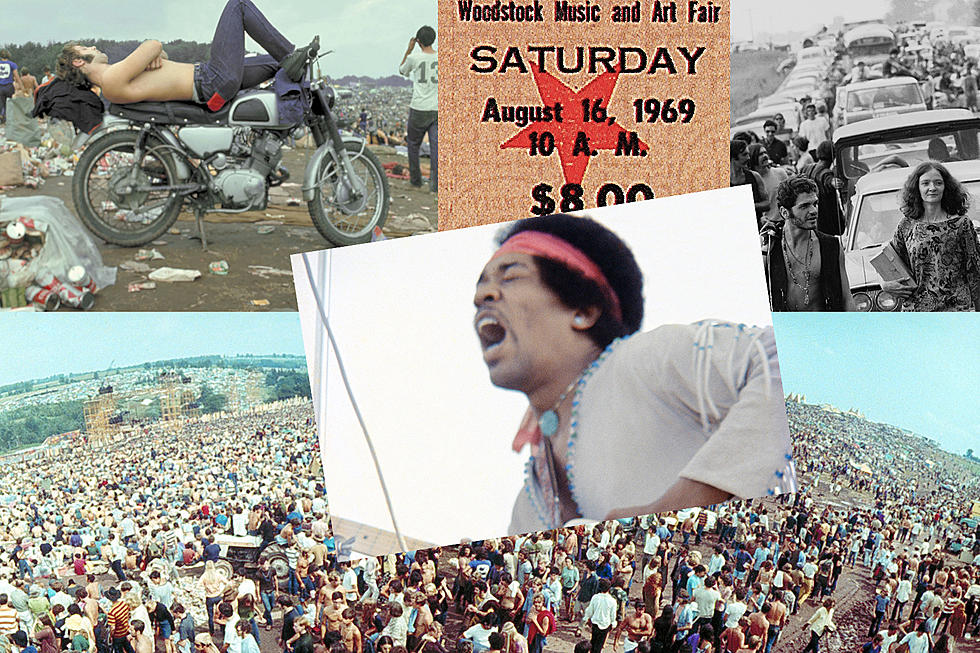

While the Woodstock name has become representative of counterculture attitudes, it’s also become somewhat representative of chaos, and not the “good” counterculture type. While it’s well-documented that Woodstock ’94 and Woodstock ’99 were both troubled events, and attempts to revive the brand for 2019 encountered severe difficulties, the reputation of the original 1969 festival remains relatively intact.

And yet, there was an incident on the afternoon of Sunday, Aug. 17, 1969, that could have become one of the biggest public tragedies of all time, and perhaps shut down the counterculture movement, and even the developing festival tradition, for good. Two words repeated through the stories sum up the potential horror: “mass electrocution.”

Billed as “An Aquarian Exposition: 3 Days of Peace & Music,” the event at Bethel, N.Y., was massively oversubscribed. Official estimates put the size of the crowd at around 400,000 but other guesses go much higher, and a state of emergency was declared because the dairy farm site could not cope with the onslaught of people who would need food, water, shelter and first aid.

By Sunday afternoon, after three days of rainy intervals tramped into mud by a million feet, it became clear that the cable supplying electricity to the stage had suffered worrying damage. For organizers Joel Rosenman and John Roberts -- who were now living on a constant knife-edge as money ran out, supplies couldn’t be delivered and the audience slid ever-closer to animalistic rioting -- it was “the bleakest moment of the festival.”

“We were sprouting walkie-talkies from every ear at that point and dealing with a dozen problems every minute or two,” Rosenman told NPR on the festival's 40th anniversary in 2009. “And on top of it all, the phone rang – the chief electrician was calling from backstage. … He sounded pretty shaky at the time, even for a man who was going through what he was going through. … I couldn’t believe he was searching for the words that he came up with. But he came up with ‘mass electrocution.’”

Rosenman and Roberts were faced with the chance that, if the music stopped, the final thread holding some form of human behavior together would snap. When the electrician said it might be possible to reroute the power supply, he was ordered to make it happen as quickly as possible.

Another account appeared in the 1979 book Barefoot in Babylon by Bob Spitz: “‘With all those kids being drenched and packed together the way they are – if the insulation goes, we’re going to have a mass electrocution,’” Rosenman and Roberts were told. Presented with the possibility of shutting down, Roberts said, “That’s impossible. … It’ll be mayhem, for sure. A half million freaked-out rabid kids running around with nothing to do would just about finish us off.” The response: “Somebody’s got to make a decision before those kids do it for us.”

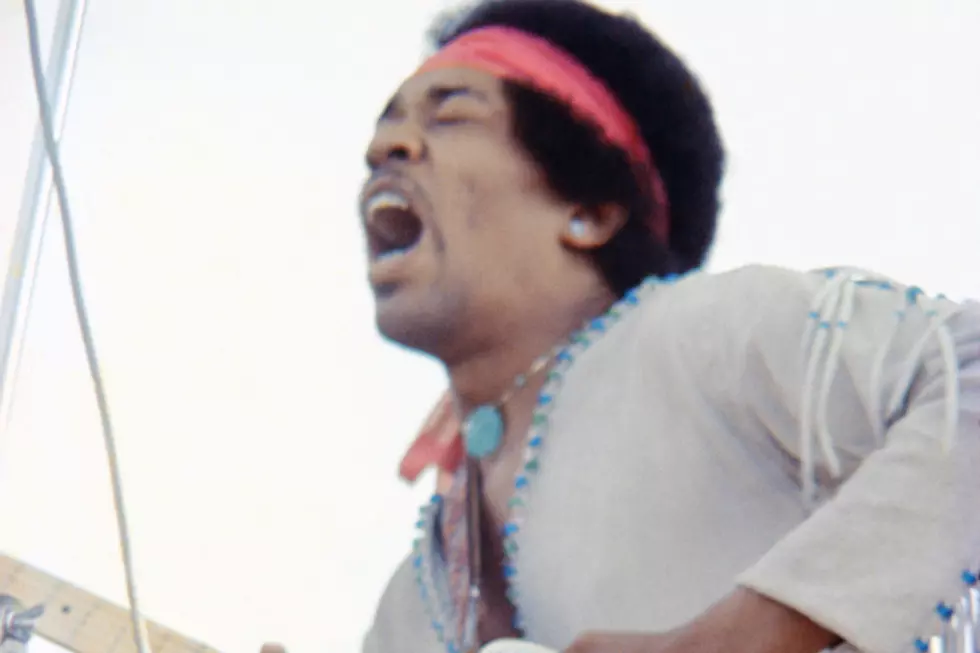

Production Coordinator John Morris was “overcome with grief” at the latest disaster. He said, “Fuck it – we’re gonna turn the power off. If we don’t, we’re gonna have French-fried musicians on that stage. … You gotta see it to believe it. All of the wires are exposed. It’s drizzling again. The lives of hundreds of thousands of people are at stake.”

After the instruction was issued to keep the music going no matter what, Spitz recounted the exchange between Roberts and Rosenman, who’d endured his inheritance being “snuffed out” as the pair wrote “bad check on top of bad check to keep the festival afloat” and now faced “the possible mass electrocution of anywhere from 300,000 to 500,000.” “What’s going on here?” Roberts asked Rosenman. “What does this mean to our lives – that we could make such a callous decision? … God, Joel, I don’t understand this thing at all.”

“Years later," Spitz continued, "Roberts would remember that precise moment and the philosophy he chose to embrace. ‘I think I had very clearly decided at that time, as a concept, that if thousands and thousands of people were electrocuted, I was going to find a reasonably swift and painless way to take care of myself. It wasn’t a suicide pact of any kind, but it was something that I knew I would never be able to live with.’” Spitz also confirmed that Rosenman had agreed to join Roberts, as they both believed their lives would be over anyway. “And they were dead serious,” the writer said.

Then, like a passing thunderstorm, it was over. Accounts vary as to how long it took for the electrician to report that the rerouting had worked and the frayed cables were gone, but it certainly felt like hours to Rosenman and Roberts.

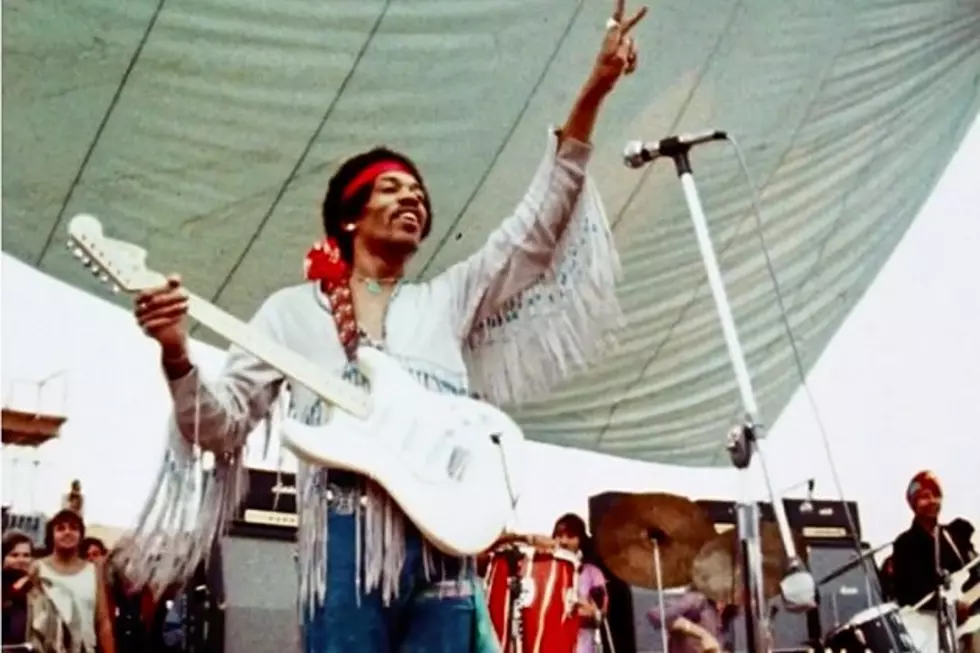

As the pair sat slumped in silent tears in the production office, Country Joe and the Fish had saved the day onstage. On being told that “the ‘electrifying’ performance they intended to put on might just be exactly that,’” the band had decided they’d play without power. Spitz reported that they “pantomimed their set with acoustic instruments … and the crowd got off on it! … It was a perfectly resilient display of impromptu showmanship that held the audience’s rapt attention while the rest of the crew insulated the stage.”

The Ringer’s Steven Hayden, who’s working on a retelling of Woodstock ’99 and included an assessment of the ’69 incident by way of comparison, argued that “the mass electrocution story has been all but written out of history, papered over by countless feel-good vibes.” He reasoned that the 1970 Woodstock movie – which made the organizers their money back and also became the defined image of the event – had “obscured the reality of a festival that, in many ways, was just as troubled and rife with problems as Woodstock ’99.”

“It’s worth noting that the song ‘Woodstock,’ Joni Mitchell’s classic anthem about a generation trying to get back to the garden, was written about a festival that was declared a disaster area," Hayden said. "She didn’t go to Woodstock; she watched it on TV. Perhaps it was always easier to love the original Woodstock from a distance. Once you get up close, the romance fades, revealing something darker, scarier and more like Woodstock ’99.”

Top 100 '60s Rock Albums

More From Highway 98.9