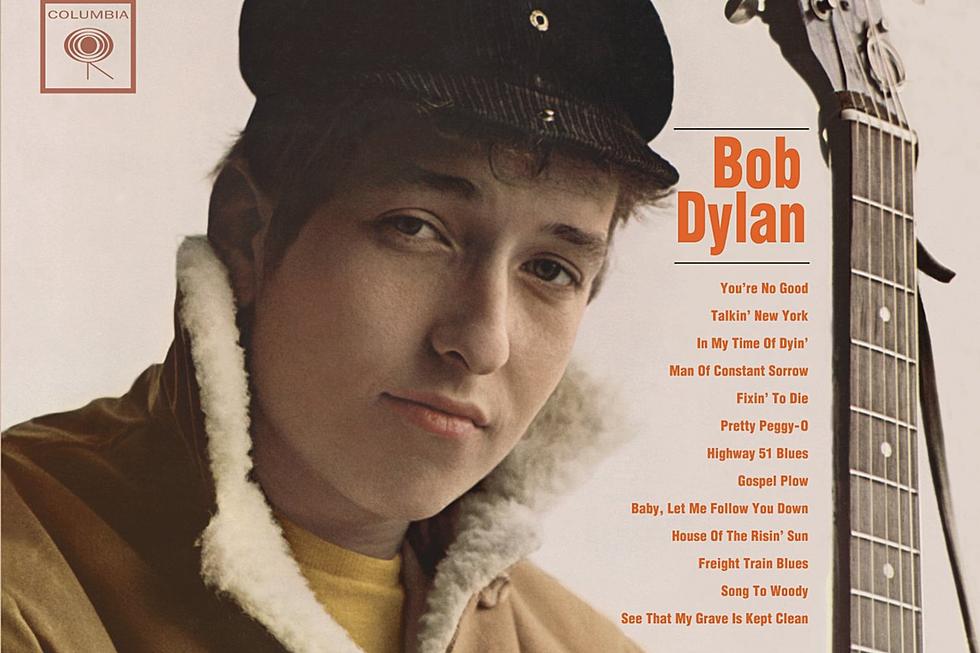

60 Years Ago: Bob Dylan’s Remarkable Career Quietly Begins

In 1962, Bob Dylan wasn't exactly what people expected the world's next musical sensation to look like.

At the time, the boyish, scrappy-looking folk singer was crashing on various couches in New York's Greenwich Village and performing short acoustic sets in the neighborhood's coffee houses. Some were intrigued by the drifter who had arrived in the city with no real credible story as to where he'd come from and why. Others assumed he'd move on just as quickly as he came.

The folk scene was already brimming with burgeoning talent and Dylan wasn't performing original material, yet he somehow seemed to stand out amongst the crowd. It helped, too, that New York Times music critic Robert Shelton had written a notably favorable review after one of Dylan's performances at Gerde's Folk City, calling him "one of the most distinctive stylists to play a Manhattan cabaret in months."

Dylan figured he'd "either drive people away or they'd come in closer to see what it was all about. There was no in between," he wrote in his 2004 memoir, Chronicles: Volume One. "There were a lot of better singers and better musicians around these places, but there wasn't anybody close in nature to what I was doing. Folk songs were the way I explored the universe; they were pictures and the pictures were worth more than anything I could say. I knew the inner substance of the thing. I could easily connect the pieces."

Then John Hammond – a Columbia Records executive who'd earlier helped bolster the careers of talents like Billie Holiday and Aretha Franklin – saw something in Dylan during a recording session for fellow folk singer Carolyn Hester.

Listen to Bob Dylan's 'You're No Good'

Dylan wasn't a particularly astounding musician or singer, and it wasn't clear whether he had any real songwriting chops. But he'd developed enough of a reputation around the Village to earn himself a spot playing harmonica for Hester, and that's where Dylan connected with Hammond. A surprising contract offer from Columbia Records followed. (Hammond would go on to sign Bruce Springsteen and Stevie Ray Vaughan, among others.)

"Columbia was one of the first and foremost labels in the country, and for me to even get my foot in the door was serious," Dylan wrote. "For starters, folk music was considered junky, second rate and only released on small labels. Big-time record companies were strictly for the elite, for music sanitized and pasteurized. Someone like myself would never be allowed in except under extraordinary circumstances. But John was an extraordinary man."

After news began to spread that Bob Dylan had secured a record deal — and not just any record deal, but one with a major label — some in the folk community who had been playing the circuit for much longer expressed agitation. How was it that this new kid on the block could snag such a prestigious position? Dylan didn't seem to notice.

"Bob was serious about the work he intended to do and paid ill-wishers no mind," Dylan's then-girlfriend, artist Suze Rotolo, wrote in 2008's A Freewheelin' Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties. "He was ready to set down on record the music he had accumulated within himself to that point."

Dylan may have been ready but he was not remotely accustomed to recording in a professional studio, as Hammond soon learned.

"Bobby popped every p, hissed every s, and habitually wandered off mic," Hammond later recalled, as reported in Clinton Heylin's Bob Dylan: The Recording Sessions, 1960-1994. "Even more frustrating, he refused to learn from his mistakes. It occurred to me at the time that I'd never worked with anyone so undisciplined before."

Listen to Bob Dylan's 'In My Time of Dyin''

Dylan “was singing in, you know, this rough-edged voice,” Columbia A&R director Mitch Miller said in No Direction Home, the 2005 documentary film by Martin Scorsese Then only 20, Dylan certainly wasn't trying to chisel his naturally untidy approach into something more clear-cut.

"There was nothing easygoing about the folk songs I sang," Dylan added. "They weren't friendly or ripe with mellowness. They didn't come gently to the shore. I guess you could say they weren't commercial. Not only that, my style was too erratic and too hard to pigeonhole for the radio – and songs, to me, were more important than just light entertainment."

Commercial or not, Dylan poured himself into the sessions, recording many of the folk, blues and traditional songs he had been performing in the coffee houses. Among them was "House of the Rising Sun," which was later made popular by the Animals, and "In My Time of Dyin,'" which Led Zeppelin would record for 1975's Physical Graffiti.

The entire recording process took place over the course of just six hours, spread out over two days, in November 1961.

"I watched Bob as he sang and saw his focus, his loyalty to the work at hand, the art he was making," Rotolo wrote. "Bob was intense, both sure and not sure of what he was doing. Afterward he'd ask: 'What do you think; what do you think?'"

Only two songs that appeared on Bob Dylan were originals. The first, "Talkin' New York," was more narrative than musical and took inspiration sonically and lyrically from a handful of songs by mentor Woody Guthrie, including "Talkin' Columbia," "New York Town" and "Pretty Boy Floyd." "Talkin' New York" chronicled Dylan's arrival in town and his experiences as he tried to establish himself in the folk scene. Dylan cut just two takes of the song, the second of which appeared on the album.

Listen to Bob Dylan's 'Talkin' New York'

The second original track, "Song to Woody," was in essence an open letter of admiration from Dylan to Guthrie, whom he visited regularly in New Jersey as the famed folk singer neared the end of his life: "I'm a-singin' you this song, but I can't sing enough / 'Cause there's not many men that done the things that you've done." Guthrie died from Huntington's disease complications in 1967.

Dylan's songwriting talent was still developing, but it was clear there was potential. "I guess it happens to you by degrees," he said later. "You don't just wake up one day and decide you need to write songs, especially if you're a singer who has plenty of them and you're learning more every day. ... It's not like you see songs approaching and invite them in. It's not that easy. You want to write songs that are bigger than life."

Multiple outtakes were ultimately not included on the final album, but did appear later on Volume 1-3 of Dylan's Bootleg Series: "House Carpenter," "He Was a Friend of Mine" and one more original song, "Man on the Street." Additionally, a cover of Guthrie's "Ramblin' Blues" was recorded but remains unreleased.

The debut was released to little critical or commercial fanfare. Bob Dylan did not chart in the U.S. at all, (making it his album to not do so), and only reached No. 13 in the U.K. three years after its release in 1965, thanks to his later popularity and U.K. tour. Dylan was, for a time, known as "Hammond's Folly" amongst the recording community, but it didn't make much difference for Columbia financially: This entire project had only cost $402 to record.

As with many lackluster debuts, however, Bob Dylan wound up earning more praise as the years went on and could be revisited with hindsight. Were it not for the confidence shown by Hammond in a completely unknown singer plucked seemingly at random from the flourishing folk scene, Dylan's career may not have made it much further beyond the doors of Gerde's Folk City.

Bob Dylan 'Bootleg Series' Albums

Why Don't More People Like This Bob Dylan Album?

More From Highway 98.9